It’s been almost two months since I last posted something here. The culprits for a stretch there were motivation and time. These last couple weeks, however, a new issue has taken hold. I feel motivated to write more technical pieces, but struggle with the level of detail necessary for my target audience. If I’m going to write about vectors, how far do I break it down? And if it gets too technical, what’s the point? Most of y’all don’t care about TF-IDF and logistic regression. But if I don’t go deep enough I’m assuming a starting point that many don’t have. Anytime I start I find myself pushing a bit deeper, and that always opens a new can of worms - how (and why) do I concisely explain fairly complex math.

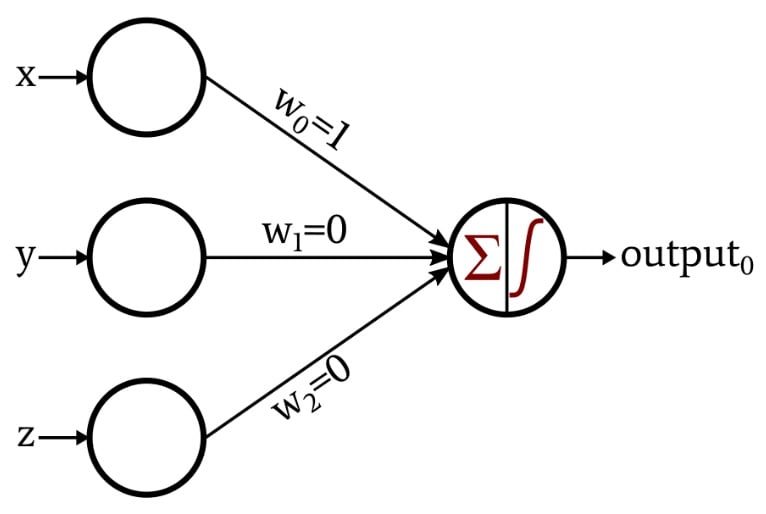

So for today I’m going to start with a perceptron. It is the smallest piece of the architecture that ChatGPT and it’s peers are based on, and perhaps by starting small and working our way up I can slowly make the points I want to make without having this struggle of zooming in and out. So here’s a perceptron:

https://www.allaboutcircuits.com/technical-articles/how-to-train-a-basic-perceptron-neural-network

In this case, let's imagine x, y, and z are numbers. For example, [2, 1, 4]. These numbers would be multiplied by associated weights w0, w1, and w2. The starting example, shown here, is [1, 0, 0]. In this case, we would multiply the incoming numbers by their associated weights, and then sum them. This would result in [2×1=2, 1×0=0, 4×0=0], 2+0+0=2. That resulting sum would then be squeezed into the space between 0 and 1 using what's called a sigmoid function, so that it can represent a probability.

That's it! Now you're probably thinking "Okay, I think I kinda get it, but what's the point?" This architecture is useless on its own. But when it is combined with repeated iterations and training data, it becomes incredibly useful. Let's now imagine that those starting numbers [2, 1, 4] represent something. Let's say for now, they actually represent a word (more on that later). Let's say the starting numbers [2, 1, 4] represent the word "cat". Let's say there are other sets of numbers that represent other words. For example, what if [3, 2, 4] represented "dog", and [6, 9, 0] represented "kitchen". Now these three examples can serve as our training data. And here is where we see the benefit of our perceptron. Our goal is to have our output probability - the result of our perceptron - reflect a probability of a given input word being an animal. So what do we do? We guess and check, repeatedly, adjusting our weights as we go. We first try with a random set of weights [1, 0, 0], and we find that it outputs probabilities of 0.8, 0.7, and 0.9 for "cat", "dog", and "kitchen", respectively. This isn't what we want. We know that "kitchen" is not an animal, but "cat" and "dog" are. So we adjust the weights, and try again. We now try with weights [0.9, 0.1, 0]. This time, we get a bit closer, our output probabilities are 0.82, 0.75, and 0.78. But still not good enough as "kitchen" is more likely to be an animal than "dog". Here's the big benefit of compute - we can just keep trying different weights until we find a set of weights that accurately gives the animals a high probability and the non-animal a low probability. That repeated process, that "guess and check" is machine learning. Now there are more sophisticated methods of finding the right weights more quickly, but this is the fundamental idea of AI. Given training data and repeated iterations, we'll eventually figure out weights that do a good job. And once we do, we will have something useful, something that inputs the word "dolphin" and outputs a prediction - a number between 0 and 1 that reflects the probability of "dolphin" being an animal.

Now if I were you, one big question would come to mind. How can [2, 1, 4] represent "cat"? The answer is in a way more complicated than anything I've explained so far. I'll attempt to tackle that in the next piece, and we'll build our way up.

Comments

Loading comments...