Okay, as I promised in the previous piece, I have some words to say on vectors. If you haven't read that one, I'd recommend checking it out before reading this one. I've long felt like vectors are the unsung heroes of AI. If a perceptron is a single circuit in an electrical system, vectors are the electricity itself, the current running from one circuit to the next.

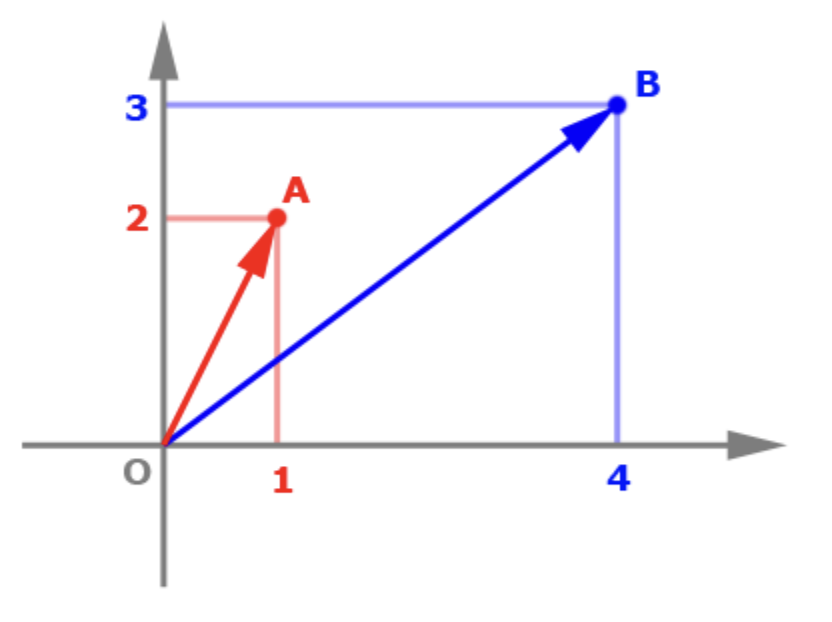

I will try to keep this piece as legible and interesting to the non-technical reader as possible. A vector itself is a fairly straightforward concept. I remember in school we learned a vector is something with both magnitude and direction. A vector is typically represented by coordinates. For example, the vector A [1, 2], and the vector B [4, 3], can be visualized in 2-dimensional space below.

Ok now bear with me here, this is where it gets slightly more complicated, but I'll do my best to make it simple. Vectors are a useful way to represent natural language. Let's give an example. Here are four sentences:

- I like cats and dogs

- I like cats

- I dislike dogs

- We like cats and rabbits

We can represent these sentences with vectors in a number of ways. Let's try just assigning each word a number, just in the order it appears. In this scenario, a 1 will respond to the first word we come across, a 2 the second word, and so on. Our sentences above could be represented as:

- [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

- [1, 2, 3]

- [1, 6, 5]

- [7, 2, 3, 4, 8]

Perhaps you can already see some potential benefits of this system. It is easy to tell that our first and second sentences are similar, as they both start with 1,2,3. We can see how our first and fourth sentences overlap in the middle, but differ in the start and the end. The shortcomings of such a system may also be obvious - the vectors above have different dimensions. Vectors of different dimensions can't be used as input data into the same perceptron, and are not useful for comparison as they don't exist in the same vector space. As vector representation mechanisms grow more complex, the vectors do a better and better job of capturing the meaning of text. One famous example is a vector representation model called Word2Vec1, developed by GoogleAI in 2013. In Word2Vec, similar words generate similar vector representations. (Similarity can be calculated by finding the angle between two vectors). For example, the vector representations of "walk" and "run" are similar when using Word2Vec, as are the representations of "but" and "however", and "Berlin" and "Germany". The most famous case I remember learning in my Master's was an example of how vector algebra also loosely held up: King - Man + Woman ~= Queen2.

I may be losing you already, but I'd like to briefly sit with this idea for one more example that is both practical and hopefully somewhat tangible. A vector used to represent a piece of text is often called an embedding. And one of the simplest useful embeddings that is straightforward to understand is called TF-IDF, or Term Frequency - Inverse Document Frequency. Let's break that down by parts. TF is just how often a specific term shows up in a piece of text. IDF is how infrequently that same specific term shows up in the entire data set. We ignore word order, and rely on the impact of rare words to differentiate between sentences. Using our examples earlier, for each sentence we would create a vector that matches the length of all the unique words present across the entire dataset.

| Sentence | I | like | cats | and | dogs | dislike | we | rabbits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I like cats and dogs | 1/3 | 1/3 | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I like cats | 1/3 | 1/3 | 1/3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I dislike dogs | 1/3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| We like cats and rabbits | 0 | 1/3 | 1/3 | 1/2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Believe it or not, that's enough. Many of the models I have built at work, including some that are still in use today, use TF-IDF as an embedding model. For me, it's somewhat intuitive when looking at the chart above that a system this simple can work. Let's imagine we are trying to classify positive vs. negative sentiment. We know that sentences one, two, and four are positive sentiment, and sentence three is negative sentiment. We then use the guess and check method we discussed in the perceptron article, adjusting the weights associated with each input column. Eventually, the perceptron is going to figure out that the words like and dislike are strong indicators of sentiment. It will heavily weight the word “like”, increasing the probability output when that word is present, and heavily downweight the word “dislike”, decreasing the probability output when that word is present. With large datasets and clearly defined classification problems, this approach scales impressively. One of the very first models I built at my current job was a relevance filter. We scrape more than a million articles from the internet everyday, and we wanted a quick way to throw out anything we were really confident was junk. I collected loads of examples of articles I knew were junk - sports stories, celebrity gossip pieces, obituaries, advertisements, how-to articles, etc. - and loads of examples of articles I knew were supply chain relevant - news articles on industrial fires, insolvencies, port stoppages, etc. I then created TF-IDF embeddings for each article, and fed them into a very simple machine learning model. With repeated iterations, it learned what was junk and what was worth keeping. And now, any new article that we scrape first gets turned into a TF-IDF vector, then passed through this filter. If it’s obviously trash, we throw it out.

Probably that's enough for now, but maybe (perhaps I'm too optimistic) you're starting to grasp how powerful this idea can be when you increase the number of iterations and the amount of training data. And if you're starting to grasp that, you're starting to understand why tech companies won't stop throwing money at AI and why Nvidia is the most valuable company in the world.

Thanks for reading!

Comments

Loading comments...